Is this art? Hettie Judah's 'How Not to Exclude Artist Mothers'

(and other parents) + how mermaid crafts used to look

One friend managed to tile a Moroccan backsplash in her Brooklyn kitchen during her maternity leave; another wrote a book. So when my sister, an artist, asked me how much work was “realistic” to get done with a newborn at her feet, I told her the truth: My 12 weeks of U.S. leave were a highly fertile time for obsessively logging feed sessions and refreshing Twitter. My baby is now 7, and I still seem to be getting very little done. The novel is in a drawer. I do not feel as funny as I once did. I hosted my last comedy show at nine months pregnant, and floated off into the beery ether. After being laid off from a sweet editing gig, I remain on the edges.

I continue to work, but my children climb onto my shoulders while I type, and grab my arm while I paint. They are fodder for work, and obstacles to my progress. I don’t know if I’m talking about a failure to create, or a failure to draw box around the things I spend time on and say “this is art.” How to explain?

The Troy post office has a couple of 1939 murals by Waldo Peirce, a bawdy artist who, despite churning through four wives, was very devoted to his kids. Ernest Hemingway once wrote an account of Peirce in a letter from Key West:

“Waldo is here with his kids like untrained hyenas and him as domesticated as a cow. Lives only for the children and with the time he puts on them they should have good manners and be well trained but instead they never obey, destroy everything, don't even answer when spoken to, and he is like an old hen with a litter of ape hyenas. I doubt if he will go out in the boat while he is here. Can't leave the children. They have a nurse and a housekeeper too, but he is only really happy when trying to paint with one setting fire to his beard and the other rubbing mashed potato into his canvasses. That represents fatherhood."

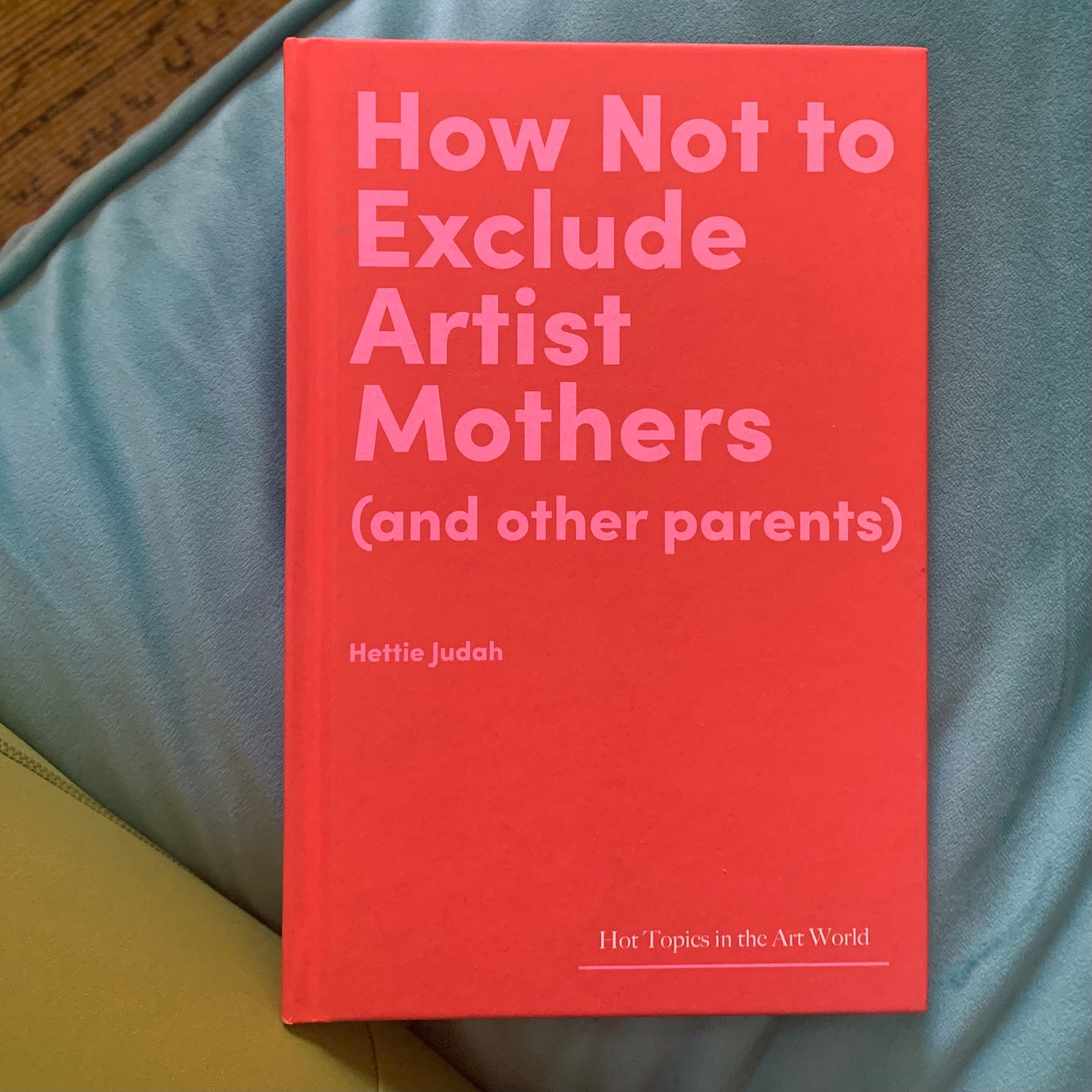

That represents art with children. But Peirce’s time in Key West with Hemingway is not the same as the “mother-shaped hole” that many parents find themselves in after baby, as Kija Benford explains to Hettie Judah in Judah’s new treatise How Not To Exclude Artist Mothers (and Other Parents), out now from Lund Humphries. The book challenges the “old cliche” that one cannot be a mother* and an artist, and presents the findings of Judah’s interviews with over 50 artists. It is — I think! — as necessary to have on the shelf [slash iPhone Kindle library at 2 a.m.] as Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born, Angela Garbes Essential Labor, Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work, and this meme of Mister Rogers.

Benford explains that the hole “starts in the breast pumping room at the art school: the small room with the metal bed, the empty walls, the window that was glued and taped with opaque plastic and blocked my view of the outside world.”

If you aren’t in a lactation closet, you’re at home. Judah spends a chapter on Lenka Clayton’s “An Artist Residency in Motherhood,” which was self-devised as “a structured, fully-funded artist residency that takes place inside my own home and life as a mother of two young children.” (I wrote about this a little in 2019 after Jenny True put me onto it — a message from one lighthouse to another!) Residencies are of course quite difficult to attend for caregivers; you typically can’t leave your children, and can’t bring them with you, though some residencies — Emily Flake’s St. Nells humor residency is one — make space for this. Clayton secured a grant for her residency, and later opened the concept up to anyone else who found it useful. During her residency in her own home, she created works like “63 objects from my son’s mouth” and “All scissors in the house made safer,” in which she spun wool around the points and handles of every pair of scissors she could find.

These works have found gallery space, but the scale of “domestic” art has been a problem in the art world, and in the pink economy of women’s media and publishing — too easy to dismiss by gatekeepers and tastemakers.

There is also the ongoing ethical problem of using your children as material, even if they are part of the scenery. Writes Judah:

“The reality of working from home as an artist parent is that you share you space with children doing children things, including bumbling around naked. This is your milieu: it is what normal looks like and feels like. What normal looks like and feels like to your growing children is an environment in which art is made, and in which spending time with your parents can mean involvement in that work.”

Artists like Sally Mann, whose photography of her children was criticized as exploitative, have had to justify their work. Taryn Simon got around this notion by creating a work, “Sleep,” that was made by taking flash photography of her children sleeping in their black bedrooms. Cusk explained in The Paris Review that “by photographing them in the dark and seeing only afterward what the camera has seen, Simon regains the objectivity of the artist, and puts it into correspondence with the child’s own objectivity.” Simon also manages to capture, in looking at her children’s bodies, “the facts of loss and of nonexistence”; your favorite subjects and mine.

Judah notes another artist who withheld the works created of her children from the public sphere until they were old enough to consent, a concession I did not extend to the child whose bath turd I wrote about several years ago, in a kind of extended artist statement around a photo of the event. Anyhow, waiting until your children are grown is part of the problem given what Judah identifies as the art world’s “cult of youth” and the need to explain resume gaps. There’s a reason all those juicy novels come about in people’s 40s and 50s — the kids are bigger — but the authors need a way back into the conversation.

Curiously, because motherhood is next door to childhood, some mothering labor takes the form of craft — elaborate cakes; those letterboards; the toilet-roll marble-runs I made early pandemic, thank u Busy Toddler — hence the issue with downplaying work of a domestic variety and scale. For me, someone who is on the amateur end of the spectrum and doesn’t have to worry about the perils of art as an asset class, I can say I feel better when I’m making something, even something shit, than I do when I’m just microwaving mac and cheese and writing about lumber prices. I personally understand the element of wanting to turn your ~ reproductions ~ (your kids) into something else. (Into a cheque worth anywhere from $25k to somewhere in the six figures, if you’re one of the celebrities or models I spoke to this 2021 New York Times piece on celebrity pregnancy announcements.) It is all tricky territory, you see, and doesn’t that make it more spicy?

This is not really a review of How Not To Exclude Artist Mothers — my take is I think you should get yourself a copy. It seems like the kind of book so full of experiences and ideas that you will take something different from it than I did, whether or not you consider yourself an ~Artist~, much as lawyers and economists and people who live in Microsoft Excel continue to love Julia Cameron. For my part, as a writer and hobbyist painter, the point is that it might be a blueprint to finding motherhood generative, though it also gets into the weeds of how artist representation and the wooing of curators works and puts out a call to those with institutional power to listen up!

Maybe the most important idea comes late in the book, and circles back to a lot of the terrain Garbes covers. Here’s Judah:

“Darren O’Donnell of the Toronto-based performance company Mammalian Diving Reflex suggested that rather than a society structured by the assumption that the typical human is self-sufficient, autonomous and competent, we might instead position vulnerability as a central idea when considering a ‘typical person.’”

How can we be more inclusive, in other words, as people go flying down the dark part of the slide where they are briefly out of view.

The question of “re-emerging” is the most common question Judah is asked about, she writes (her book takes its name from a report she was commissioned for back in 2021). “The best I can offer is a vague set of suggestions: work from a studio complex rather than from home so that you have other artists around you; form a mutually supportive group that promotes out another’s work; collaborate; organize shows; apply for residencies; work like a fury.”

To circle back to the top of the post, I recently executed an idea dreamed up by MWJ, fount of brilliance, in the ecosystem of April Daniels Hussar, who, aside from being a certified brassy dame, is so smart and funny and charming that good ideas happen in her presence (you should be so lucky to work with and/or be edited by her). What if those maddening-yet-vital breastpump filters… as jewelry, went the thought, and maybe four years later, the conclusion is finally in the mail back to the originators, in the form of Femo with some brass studs and backs.

*Hettie Judah includes people of all genders in the treatise, and notes the historic devaluing of work by cis-female artists with children.

Is this art?

We had, for unknown reasons, an intact egg lying on our front lawn, and Noodles picked it up and goes "where did this come from?"

Japhy looked at him like he was an IDIOT and goes "from a CHICKEN."

Goodies

There have been a lot of good reminiscences of mountaineer Hilaree Nelson, but Andrew Bisharat’s got me:

In so many areas of life, we like to believe that we can “create our own luck,” as if the right amount of determination, hard work, perseverance, and optimism necessarily brings our preferred outcomes. And yet time and time again, that idea that we’re in control of our fates crashes headlong into reality.

This becomes all the more maddening when you see people who aren’t skilled, or at least who aren’t as skilled as others who get less lucky, escape one near miss after another. Meanwhile, those whose skill is unmatched, people like Hilaree, find that the cost of playing in the mountains is that in one moment, one cruel and unlucky moment, all that skill isn’t enough.

And Natasha Lennard on the limits of “certainty”:

I’m hardly alone in bristling at the constant, breezy invocation of uncertainty. It has become a joke of sorts: think of Brecht, parodied: In the uncertain times, will there also be tweeting? Yes, there will also be tweeting. About the uncertain times.

…

Nor is your certainty about the existence of your hands, and other everyday external objects, reached through theoretical deduction.

Thank you for reading KAFKA’S BABY! Do share if you feel like it! And if you thought this was a bit of alright, you might like some previous KAFKA’S on:

<3 <3

This is so very good! And I hear you about the disappearance of wokkawokkafunnybonemojo. Woof.

I had a project shelved that involved an artist who was grappling with parenting and maintaining a creative practice. A lot of what you're talking about was covered!

Thanks for the economists shout out!! (As I rock a sick toddler to sleep while working on my phone and listening to the PNG PM give a speech 😅💪)